The Forgotten Divide

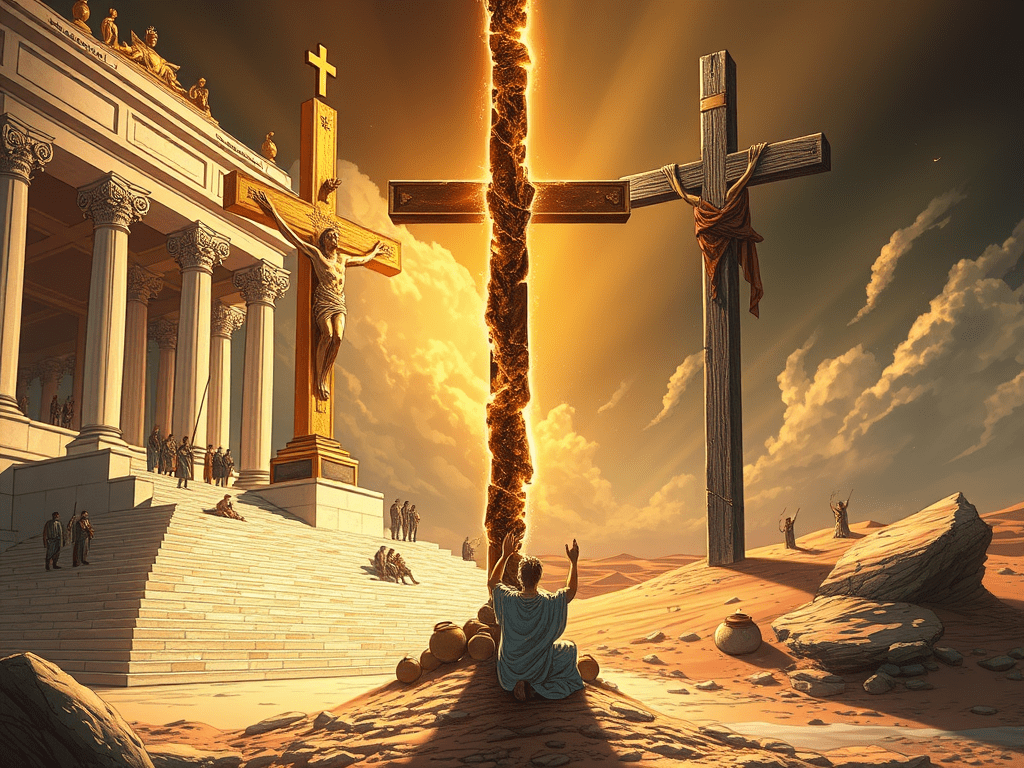

There was a time when to follow Christ meant to bleed, to vanish, to lose everything and rejoice. But something changed. Something tectonic. And when it did, the Church stood at a crossroad, holding in one hand the cross… and in the other, a scepter.

The First 300 Years

For the first three centuries, Christianity was a movement of fugitives, not emperors. It spread in secret, whispered through alleys, preached at risk of death. These early Christians had no armies, no temples, no political pull—only the aching hope of resurrection, and a fierce refusal to worship Caesar. They believed, without compromise, that the Kingdom of God did not resemble Rome.

0-50 AD, Born in Chains

The earliest decades of Christianity were defined not by formal doctrine or ecclesiastical structure, but by raw, lived persecution. The faith’s origin flickered within the synagogues and alleyways of Jerusalem, where followers of Jesus were viewed not as heretics, but as a troublesome offshoot of Judaism.

The Roman authorities, concerned more with taxes than theology, largely ignored this religious friction, leaving the burden of enforcement to the Jewish elite. Thus, the Sanhedrin, the ruling Jewish council, took it upon themselves to extinguish what they saw as a dangerous distortion of Mosaic law.

“Persecutions were sporadic, mostly fueled by religious leaders and not Roman Imperial decree.”

Among these persecutors rose Saul of Tarsus, a man consumed by zeal. Picture a man cloaked in zeal, dragging Christians from homes by torchlight—this was the tone of the times. Saul obtained legal authority from the high priests to imprison followers of “the Way,” targeting gatherings and infiltrating house churches.

It was during this period that Stephen, a deacon known for his bold preaching, became the first Christian martyr. Dragged before the Sanhedrin, Stephen gave a prophetic defense of the Gospel and was executed by stoning while Saul looked on with approval.

“And the witnesses laid down their clothes at a young man’s feet, whose name was Saul” (Acts 7:58).

The means of arrest during this period were both formal and informal: temple guards, religious tribunals, and public denunciations from neighbors or synagogue leaders. Once arrested, the early believers faced a range of punishments. Flogging was common—39 lashes, carefully counted to stop just short of the 40th, which symbolized death. Peter and John were imprisoned multiple times (Acts 4–5), not for crimes against Rome but for proclaiming Jesus as Messiah. Despite miraculous escapes and growing crowds, the opposition hardened.

For those deemed most dangerous—or most visible—the punishment escalated to execution. Stephen was stoned to death, a method prescribed under Jewish law for blasphemy. Peter, according to tradition, was crucified upside down in Rome, echoing his Savior’s death but requesting a more humbling end. Paul, as a Roman citizen, was beheaded—a quicker and more “respectable” execution, but no less final.

“I am ready not only to be bound, but also to die at Jerusalem for the name of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 21:13).

These first decades are often remembered through the lens of miracles and mission, but to follow Jesus meant risking everything—freedom, family, flesh, and breath. There were no churches, only rooms; no vestments, only rags; no pulpits, only prisons. The early Christians were not merely believers—they were the persecuted, the hunted, and, for many, the executed.

Their blood, spilled quietly under Roman indifference and Jewish hostility, became the seed of something Rome itself could never contain.

50-112 AD, Living Torches

The second half of the first century, 50–100 AD, marks a profound shift in Christian persecution—from localized religious outrage to sanctioned imperial violence. What began as scattered hostility from synagogues and communities transformed into state-driven terror.

This transformation was catalyzed by one of the most infamous events in Roman history: the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD.

“The Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD gave Nero the excuse he needed to scapegoat Christians, launching the first empire-sanctioned persecution.”

As flames consumed the city, suspicion fell on Emperor Nero himself. Seeking a scapegoat, Nero cast blame upon the Christians—already a suspicious sect rumored to engage in strange rituals and defiance of imperial cults. He accused them of arson, impiety, and social destabilization.

What followed was not justice, but a spectacle of cruelty.

[64 AD] [NERO’S BONFIRE]

“Rome burns — a crimson horizon. Christians, dipped in pitch, become human torches in Nero’s gardens. The coliseum echoes with screams and snarling beasts. Crosses bloom along roads like grotesque trees.”

Christians who refused to worship the emperor or offer incense to Roman gods were considered enemies of the state. Compounding suspicion were grotesque misunderstandings of Christian rituals: the Eucharist, interpreted as cannibalism, and the use of terms like “brother” and “sister,” misconstrued as incestuous cult behavior.

Once arrested, believers endured a new wave of punishments meant to humiliate and dehumanize. Flogging, branding, and public exile became standard—John the Apostle himself was banished to the island of Patmos (Revelation 1:9). Public shaming and confiscation of property followed, not merely as punishment, but as a tool to isolate and impoverish the community.

Christianity was not just persecuted—it was being socially erased.

When punishment escalated to execution, the empire showed no restraint. Crucifixion returned, not just as execution but as torture. Christians were thrown to wild beasts in amphitheaters, their deaths framed as entertainment. Burning alive became a favorite horror, especially under Nero. In his gardens, he drenched Christians in oil and lit them on fire to illuminate his feasts.

“Christians, dipped in pitch, become human torches in Nero’s gardens.”

By the end of the century, persecution settled into a gruesome bureaucracy. The Roman Empire didn’t yet fully outlaw Christianity, but it treated the faith as dangerous. This is captured powerfully in 112 AD, when Roman governor Pliny the Younger wrote to Emperor Trajan for guidance.

[112 AD] [TRIAL & TESTIMONY]

“Pliny writes to Trajan: ‘Should we kill them if they refuse to sacrifice?’ A scroll hovers midair — the imperial response: ‘Yes, but no witch hunts.’ Christians are given three chances. Three denials, or death.”

Trajan’s response set a precedent: Christianity was not to be actively hunted, but once discovered, it demanded loyalty to the Empire—or death. The early Church, once invisible and ignored, had become too bold, too numerous, too defiant to remain beneath notice. It had become Rome’s problem.

And yet, this era gave rise to the image that would define Christian identity for centuries: faith standing defiantly in the fire. These were not warriors, but witnesses—martyrs—whose deaths spoke louder than any decree.

100- 150 AD, The Atheists

The opening decades of the second century, 100–150 AD, revealed a new evolution in Christian persecution: systematic interrogation paired with cultural suspicion. Christianity, no longer dismissed as a mere branch of Judaism, was now recognized by the Roman world as something altogether different—exclusive, stubborn, and dangerously disruptive.

The refusal of Christians to participate in Roman religious life—especially the worship of the emperor—was seen as both sacrilege and treason.

“They were accused of hating the human race.” – Tacitus, Annals 15.44

Roman elites viewed Christians as secretive, irrational, and disloyal to the ideals of Roman unity. In amphitheaters and public courts, crowds demanded their blood.

The state, uneasy with popular unrest, began using interrogation and forced confession as a way to control the spread of this growing sect. Arrests often began with anonymous accusations or neighborhood rumors—any whisper of noncompliance could trigger an inquiry. Once apprehended, Christians were interrogated with opportunities to recant, often under the looming threat of execution.

Those who refused to deny Christ were subjected to torture, not necessarily for information, but to test the sincerity of their faith. They were commanded to offer incense to the emperor’s image or swear oaths to Jupiter—rituals many believers refused on pain of death. Their refusal to participate in Rome’s religious framework earned them a sinister title: “atheists”, because they rejected the gods of the empire.

“They call themselves believers, yet deny the gods, the sacrifices, the empire itself.”

For Roman citizens, beheading was the common method of execution—swift, cold, final. For others, especially those meant to serve as warnings, deaths came by wild beasts in the arenas or by burning at the stake.

These were not isolated incidents.

They were public displays of state power over faith. Christian communities learned to live with the possibility of death at any hour—and to die without renouncing.

150-200 AD, Mob Mentality

In the following decades, 150–200 AD, persecution took a more chaotic turn. The state no longer held a firm grip on enforcement; instead, mob violence surged, fueled by suspicion, propaganda, and spontaneous rage. Local officials, often indifferent or fearful of the crowds, allowed lynchings, beatings, and public executions to unfold unchecked. The empire needed no formal edicts—fear and superstition did the work.

This period saw the emergence of the term “superstitio prava et immodica”—a “corrupt and excessive superstition”—to describe Christianity. It wasn’t seen as religion. It was seen as infection. Long imprisonments, deliberate starvation, and brutal torture were employed to force apostasy. Some endured isolation for years. Others were publicly humiliated—mocked, beaten, and made into examples for the masses.

“If they will not burn incense, then let them burn instead.”

Public executions were no longer just state mandates—they were entertainment. Gladiatorial games often featured Christians as the condemned, forced to face wild animals or death by other means, all under roaring crowds. Hot irons and racks twisted bodies until limbs gave way. The Christian body was treated as a canvas for Roman vengeance.

During this time, Justin Martyr—a Christian philosopher—stood at the intersection of faith and philosophy. He wrote boldly in defense of Christian morality, pleading with emperors to judge Christians not by rumor, but by truth.

Yet despite his eloquence, he was arrested and condemned. He died by beheading, proving that even reason could not shield truth from empire.

“If we are executed for the name of Christ, we are not dying but living.” – Justin Martyr, First Apology

This half-century was not defined by imperial policy but by cultural rage. Christians became symbols of defiance, their very existence a challenge to Rome’s gods, its laws, and its pride. Yet through prisons, beasts, and flame, they endured. The empire still misunderstood them—but they no longer misunderstood themselves.

250-313 AD, Bloodbath

Between 250 and 313 AD, the persecution of Christians reached an intensity unmatched by anything before it. This was not a scattered storm, but a deliberate, empire-wide bloodbath, engineered by emperors desperate to reassert control over a fractured and failing Rome. As the empire’s gods seemed silent and its borders crumbled, Christians—seen as impious and obstinate—became convenient scapegoats.

Faith was now treason. Baptism, rebellion. The Church, a threat to imperial unity.

[203 AD] [THE LIONS ROAR]

“A young woman, Perpetua, cradles her newborn before being led into the arena. Her diary survives, her flesh does not. Felicitas follows — joy in chains.”

Under emperors Decius, Valerian, Diocletian, and Galerius, persecution transformed into cold policy. In 250 AD, Decius issued an edict requiring all citizens to prove their loyalty by offering sacrifice to the Roman gods. Those who complied were given a certificate known as a libellus. Those who refused—particularly Christians—faced torture or death.

[250–260 AD] [CERTIFICATES OF SACRIFICE]

“Libelli flutter like dying leaves. Christians queue to sign or die. Some cave, others vanish into catacombs. Martyrs rise. Apostates weep.”

The strategy was simple: destroy the faith by destroying its foundation. Informants were rewarded, bishops were targeted, and leaders were publicly humiliated or executed. Elderly saints were beaten, deacons tortured, entire congregations scattered. Many believers were sentenced to forced labor in mines, where starvation and disease killed slowly. Prisons became graves.

Executions became acts of imperial theatre. Beheading and crucifixion were standard. Others faced roasting on griddles—like St. Lawrence, who allegedly quipped, “Turn me over, I’m done on this side.” Some were tied to bent trees, released, and torn apart.

[303–311 AD] [DIOCLETIAN’S PURGE]

“Imperial edict like a thunderclap: ‘Destroy their scriptures. Level their churches.’ Smoke pours from burning scrolls. Bishops chained, flayed, or buried alive. The sword is sharpest in this dusk before dawn.”

This campaign—known as the Great Persecution—was Diocletian’s brutal attempt to eradicate Christianity entirely. It wasn’t just about killing believers; it was about erasing their memory. Churches were demolished, Scriptures burned, leaders hunted and executed. Rome, in its twilight, swung wildly to preserve what little light it believed remained—never realizing it was stamping out the very light it needed.

313 AD, The Cross Ascends

Edict of Milan 313 AD

Even as the empire grew tired of its own violence, one man would change everything. After Diocletian retired, Galerius, on his deathbed in 311 AD, finally relented.

“Let them exist,” he wrote. “We have failed to kill their faith.”

In 313 AD, the empire reversed its course completely.

[313 AD] [THE CROSS ASCENDS]

“Constantine and Licinius shake hands beneath a rising sun. ‘Let Christians be free.’ The Edict of Milan is signed — ink instead of blood, finally. A cross appears in the sky — not as a target, but a symbol of triumph.”

The Edict of Milan legalized Christianity, restored confiscated property, and declared religious liberty across the empire. Constantine, once a general marching through civil war, now held the reins of empire—and with them, the Church’s future.

For the first time in history, Christianity stepped out of the catacombs and into the courts of emperors.

- Churches were returned and rebuilt—now with marble columns and imperial funds.

- Bishops sat beside generals, held state offices, and influenced imperial law.

- The same empire that crucified Peter … now painted him in golden halos.

In an instant, the persecuted became privileged.

The Great Fork

But not everyone joined the parade.

Some remembered the martyrs, the caves, the faith untainted by gold. Others looked around and wondered—had they emerged victorious… or had they been absorbed?

What came next would divide the Church forever: some would rise with the empire, and others would flee into the wilderness, carrying the memory of blood and flame as a sacred trust.

Some looked at the Church’s new wealth, its state-sanctioned power, its alliances with emperors—and recoiled. To them, this wasn’t a victory. It was a seduction. The Church, they believed, was being offered the world in exchange for its soul.

Refused to Rise

The history we’re taught is often written in marble—etched by empires, councils, and victorious crowns. Rome’s version of Christianity, later adopted and adapted by England, Byzantium, and the monarchies of the West, tells a story of triumph: the persecuted Church finally legalized, the faith victorious, the cross lifted beside the eagle.

These lesser-known Christians didn’t join the empire’s ascent. They didn’t sit on thrones or build sanctuaries of stone. They heard the applause of Constantine’s court and felt only unease. They saw bishops become magistrates, martyrs replaced by magistrates, and the poverty of Christ exchanged for marble and silk.

So they fled.

Not in bitterness—but in hunger for holiness. They vanished into the deserts, the mountains, the tombs, and caves. They ran from comfort, because comfort dulled the fire.

While Constantine was building basilicas, these saints were hollowing out lives in caves. They weren’t rejecting the Church—but they feared what the Church might become when it stood too close to power. They wanted to follow Christ as he walked: poor, broken, solitary, free.

And so began the Desert Fathers and Mothers.

Enter the Desert Saints

One of the earliest and most revered was Anthony of Egypt. Born into wealth, he read the words of Jesus—“Sell all you have, give to the poor, and follow me”—and actually did it.

“A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him, saying, ‘You are mad—you are not like us.’”

— Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Anthony 25

Around 270 AD, he left the city and wandered into the wilderness, seeking solitude with God. He lived in abandoned tombs, then in a cave, eating almost nothing, praying unceasingly. He battled inner demons, not with sword or fire, but with silence, fasting, and surrender.

“Men are often called wise according to the standard of this world. But the real wise man is he who is wise in God.”

— Life of Anthony, 72

Others followed.

By the early 4th century, the deserts of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine were dotted with cells of silence—hermits, anchorites, and small communities of monks and nuns who lived without property, ambition, or pretense. They embraced a life of renunciation, not to escape suffering, but to meet God in its depths.

- They slept on the ground.

- Ate only bread, roots, or nothing at all.

- Some went years without speaking.

- Some wept every day for their sins.

- And still others healed the sick, cast out demons, or simply listened.

“A monk’s cell is the furnace of Babylon,” one desert father said. “If he remains there, God walks with him.”

These weren’t philosophers. They were burning hearts in bodies of dust.

While bishops were seated in councils and debates were codifying doctrine, the cave saints were writing theology with tears. Their lives became the gospel: poverty, humility, compassion, endurance.

- They didn’t wear vestments. They wore rags.

- They didn’t speak of power. They spoke of surrender.

- They weren’t trying to convert the empire—they were trying to become like Christ.

Forgotten Holiness

As Christianity ascended into marble and empire, the world forgot something. It forgot the stillness. The burning silence. The face of Christ etched not in stained glass, but in the lines of the poor, the broken, the hidden.

History remembers the Church that rose with the world. But perhaps it is time to remember the Church that fell with Christ.

The empire wrote laws. These saints wrote wisdom in ash and breath.

Their words were not for the powerful. They were whispers to the soul, echoes of a way of life that looked more like Christ than anything rising in Constantinople or Rome.

These were not Roman Catholic saints canonized by courts.

They were the un-canonized, the unwanted, the unknowable.

And yet they may be the most Christ-like voices we’ve never heard.

Let them speak now—not as doctrine, but as direction.

Anthony of Egypt (c. 251–356 AD)

Anthony, the father of desert monasticism, had no need for eloquence. He lived in silence longer than most live in years. This saying is not a rebuke. It’s a mirror. When holiness becomes rare, sanity will look like madness. In a world where the Church shook hands with empire, Anthony turned and walked deeper into the desert.

“Do not admire the rich or fear the powerful. They have their reward here. You, seek the Kingdom.”

He refused the court. He sent no blessings to crowns. When Constantine’s sons wrote to him, he answered with humility—but did not visit. The Church had stepped into Caesar’s halls. Anthony stepped further into Christ’s shadow.

Syncletica of Alexandria (4th century AD)

“It is easy to begin the spiritual life, but hard to persevere in it.”

One of the few voices among the early Mothers of the desert, Syncletica gave up a life of wealth and withdrew into ascetic obscurity. She didn’t just teach women—she taught humans how to burn without being consumed.

“There are many who live in the mountains and behave like people in the towns, and they are wasting their time. It is better to live in a crowd and keep calm, than to live in solitude with a harassed mind.”

She wasn’t romantic about retreat. Holiness wasn’t about place—it was about presence. About watching the heart. You can be in a cave and still be consumed with vanity. You can be in a city and still walk with God.

Macarius the Great (c. 300–391 AD)

“The heart is but a small vessel; yet dragons and lions are there, and there also are God and the angels, life and the kingdom, light and the apostles, the heavenly cities and the treasures of grace—all things are there.”

Macarius takes the entire empire and reduces it to the battle within. No temple, no title, no emperor can contain the Kingdom. It is hidden in the chest of the humble. That was the scandal of the desert: they believed God lived in silence, not in senate halls.

“If you see someone falling asleep during prayer, cover him with your cloak.”

While bishops argued over theology, Macarius offered mercy to the weak. His God was not angry. His God was kind. He believed compassion was more powerful than correction.

Amma Theodora

“Let us strive to enter through the narrow gate. Just as the trees, if they have not stood before the winter’s storms, cannot bear fruit, so it is with us. This present age is a storm, and only those who are deep-rooted will endure.”

This is not passive mysticism—it’s defiant tenderness. Theodora stood in the whirlwind and called it what it was. The Church could not afford softness dressed in gold. It needed roots—roots that burrowed into suffering, into humility, into Christ.

While empires wrote the theology of dominance, these saints whispered the theology of descent.

Two Directions

By 400 AD, Christianity stood in two places.

- In the palaces and halls of Rome—adorned, defined, and enshrined in law.

- And in the deserts and caves—mystical, surrendered, raw, and holy.

One path was lifted in gold.

The other vanished into dust.

The cross was now engraved in imperial seal, but in some hidden corners, it was still being carved into backs.

This was the great divide.

Not between heresy or orthodoxy.

But between rags or riches.

Between power or purity.

Between the Church that rose, or the Church that refused.

Jesus once stood on a mountain and gave the world his heart. What he spoke could never serve a crown.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit…

Blessed are those who mourn…

Blessed are the meek…

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake.”

— Matthew 5:3–10

He did not say: Blessed are the influential.

He did not say: Blessed are the bishops of Rome.

He never promised a throne—only a cross.

“Woe to you who are rich,

for you have already received your comfort.

Woe to you who are well fed now,

for you will go hungry.

Woe to you who laugh now,

for you will mourn and weep.”

— Luke 6:24–25

One path built basilicas.

The other lived in tombs.

“Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests,

but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.”

— Luke 9:58

The prophets knew this too. They had seen kingdoms drape themselves in false righteousness, and they thundered against it.

“What are your multiplied sacrifices to Me?” says the Lord.

“I have had enough of burnt offerings…

Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean…

Learn to do good;

Seek justice,

Reprove the ruthless,

Defend the orphan,

Plead for the widow.”

— Isaiah 1:11, 16–17

And again:

“They dress the wound of my people as though it were not serious.

‘Peace, peace,’ they say, when there is no peace.”

— Jeremiah 6:14

There has always been a danger of a religion that serves the state, the sword, or the system. And there has always been a remnant that walks away from it.

Both still exist.

One path still seeks position, influence, victory.

The other path still weeps, still prays, still burns in silence.

One path asks, “How can we win the world?”

The other asks, “How can I lose myself?”

“If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me.”

— Mark 8:34

These are the two directions.

Both wear the name Christian.

But only one walks the road Christ walked.

Sources & References

Scriptural References (ESV / KJV / NASB):

- Acts 7:58 – The martyrdom of Stephen and the mention of Saul of Tarsus

- Acts 4–5 – Arrest and imprisonment of Peter and John

- Acts 21:13 – Paul’s declaration of readiness to die for Christ

- Matthew 5:3–10 – The Beatitudes (Sermon on the Mount)

- Luke 6:24–25 – Woes to the rich and comfortable

- Luke 9:58 – The Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head

- Mark 8:34 – “Deny yourself, take up your cross, and follow me”

- Isaiah 1:11, 16–17 – Prophetic rebuke of empty sacrifices

- Jeremiah 6:14 – False prophets crying “peace”

- Revelation 1:9 – John exiled to Patmos

Primary Historical Sources:

- The Annals by Tacitus – Roman views on Christians, especially after the fire of Rome (Book 15, Chapter 44)

- Pliny the Younger’s Letters to Emperor Trajan (c. 112 AD) – Imperial policy on Christians

- The Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas (c. 203 AD) – Eyewitness diary and account of early martyrdom

- Justin Martyr, First Apology – Christian philosophical defense and statement of faith under persecution

- The Life of Saint Anthony by Athanasius (written c. 360 AD) – Biography of Anthony of Egypt and early monasticism

- Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum) – Collected wisdom from early Christian ascetics

Modern Historiography & Commentary:

- The Rise of Christianity by Rodney Stark – Social, economic, and political analysis of the early Church

- Church History in Plain Language by Bruce L. Shelley – Accessible summary of Church development

- The Early Church by Henry Chadwick – Academic but readable treatment of early Christianity

- The Desert Fathers: Sayings of the Early Christian Monks translated by Benedicta Ward – English rendering of ancient monastic wisdom

Note on Sources: Much of this article draws on a blend of primary early Christian texts, biblical scripture, and historical consensus about imperial Rome, martyrdom, and the post-Edict transformation of the Church. Some Desert Father sayings are paraphrased or summarized from traditional attributions and may vary slightly across translations.

Leave a comment